Estimated reading time: 3 minutes

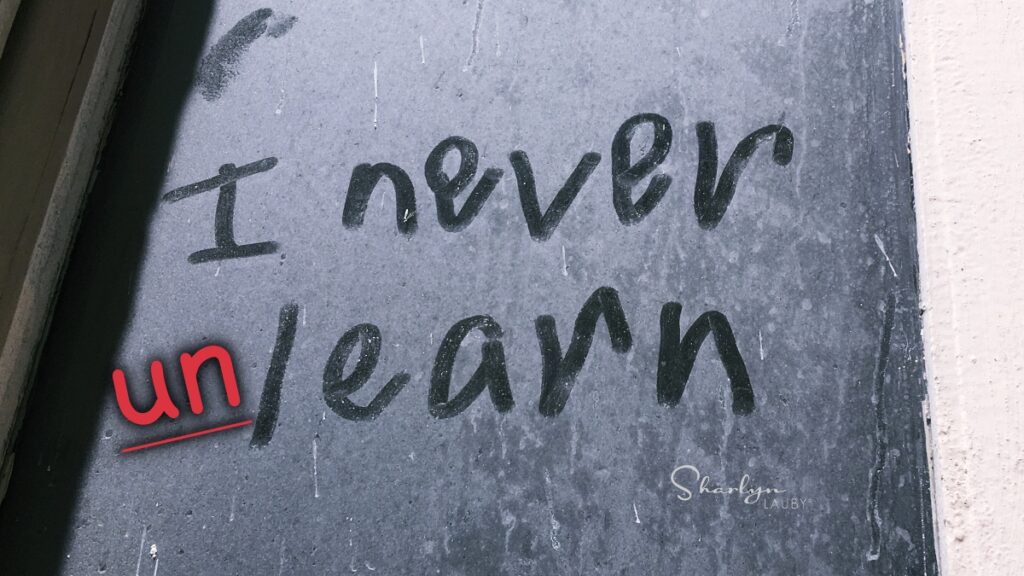

I’ve been seeing a few articles recently about “unlearning”. There was one from Lifehacker titled “What You Should ‘Unlearn’ to Actually Succeed at Work” and the another from Harvard Business Review that was focused on “Redesigning How We Work”.

While the HBR article wasn’t exclusively focused on unlearning, the conversation about hybrid work reminded me that organizations shouldn’t expect employees to simply unlearn everything they’ve been doing for the past three years with a snap of the fingers. We’ve developed new habits and ways of getting things done. Employees should be given time to unlearn and relearn.

Then it occurred to me that organizations really don’t spend much time teaching unlearning. And maybe it’s time we start. The first thing that came to mind when I think of unlearning is using something like Lewin’s Change Model (unfreeze – change – refreeze). You could even call it unlearn – practice – relearn.

During the UNLEARN phase, employees realize they need to change their behavior. This could happen a couple of ways. First, the organization decides they’re going to implement a new policy, procedure, or process. Or second, the employee realizes that something they currently do doesn’t work anymore. Either way, the employee needs to learn a new way of doing something.

Example: Let’s say we manage a restaurant. Just hired a new server. The server has experience at several local restaurants. But they need to learn our restaurant’s processes, policies, and procedures. The new server needs to unlearn the way they did things at their former employer and relearn our system, while still understanding the concepts of restaurant service.

In the PRACTICE phase, the employee receives education and training on the new activity. They’re given an opportunity to practice. This could take place in a formal training environment (like classroom training) or informally in on-the-job training. Employees are still given time to adjust to the new way. It’s possible they might make mistakes.

Using our new server example, it’s possible that they might mess up how they key in a customer’s order because their former employer’s system was different. Or they might ask some questions about “Well, what do I do if a customer does ABC? Because at my last job, we did this.” Honestly, this could be very helpful. Asking questions means the employee is thinking about unlearning and what behaviors they should keep using.

Finally, the RELEARNING phase allows the employee to move forward with the new behavior. It’s important that managers provide support, coaching, and feedback to let the employee know how they’re doing. If the employee will start to be held accountable for “knowing” the new behavior, the manager needs to tell them.

Our new server is doing a great job and hasn’t had any mistakes lately. While we cannot expect everything to be perfect, both the manager and the new server feel comfortable that performance expectations have been communicated and trained. Moving forward, the server will be expected to follow the company’s performance standard.

Organizations might be very tempted to tell employees “Effective tomorrow, here’s the new procedure.” and not give anyone a chance to unlearn the old procedure. Not only does unlearning create buy-in for the change but it gives employees a chance to practice, which can improve their overall performance. And isn’t that what organizations want – good employee performance? Because good performance = good bottom-line.

Image captured by Sharlyn Lauby while exploring the streets of Havana, Cuba

18